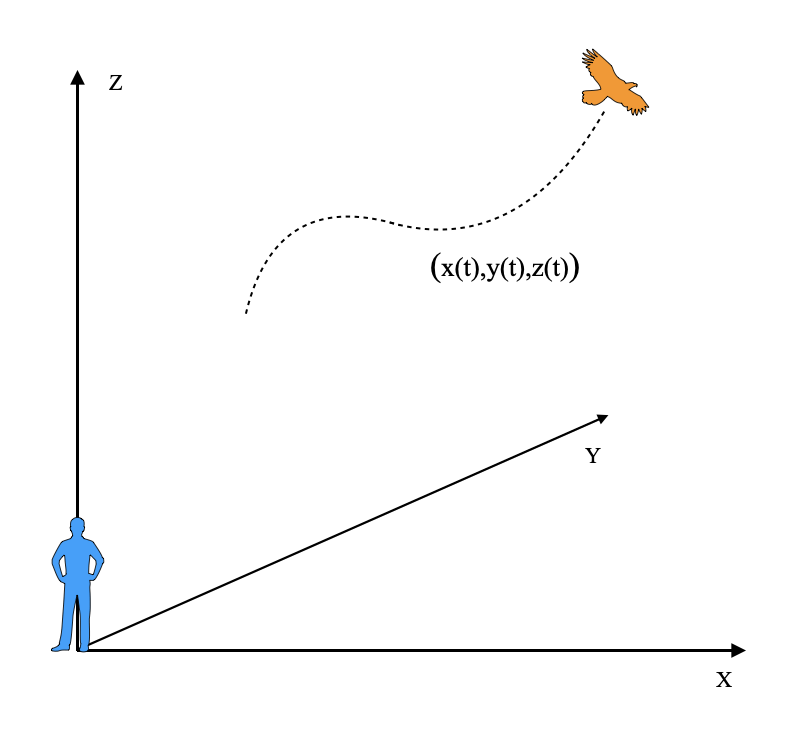

Suppose you are interested in following the trajectory of a flying bird. To do so, you would need to specify the location of the bird in 3-D space at each moment in time. What would that require? Well, it requires a spatial coordinate system, assigning a unique address to each point in space, and a clock, assigning a “time address” to each moment in time. Let’s construct this coordinate system.

Constructing spatial coordinates

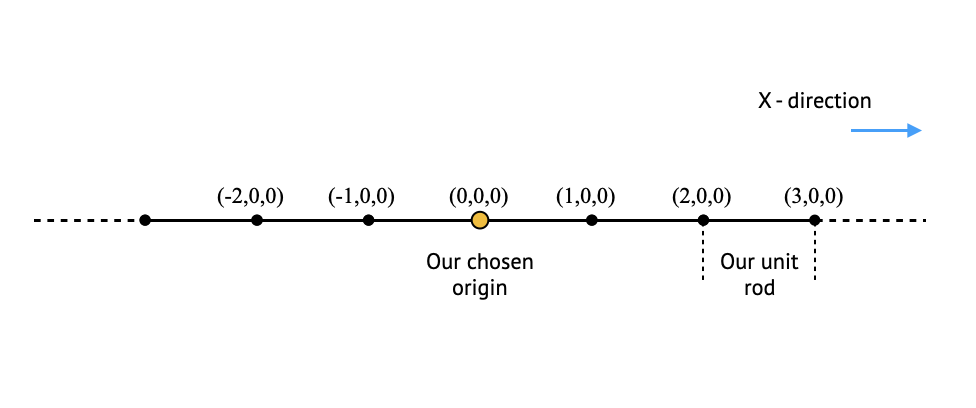

To construct a spatial coordinate system, all we need is a rod and a way to measure angles. We can define the length of the rod to be one unit of length. By choosing an arbitrary origin point in space, we can place the rod in an arbitrary direction such that one of its ends is at the origin. The other end will mark a location in space which we will refer to as “one unit in the X direction”, and label it as $(1,0,0)$. By moving the rod in the same direction in which it is oriented, such that the end previously placed at the origin is now placed as $(1,0,0)$, we get that the second end is now located at a new point in space which we will label as $(2,0,0)$: “two units in the X direction”. Following this step again and again will map out the entire “X axis”:

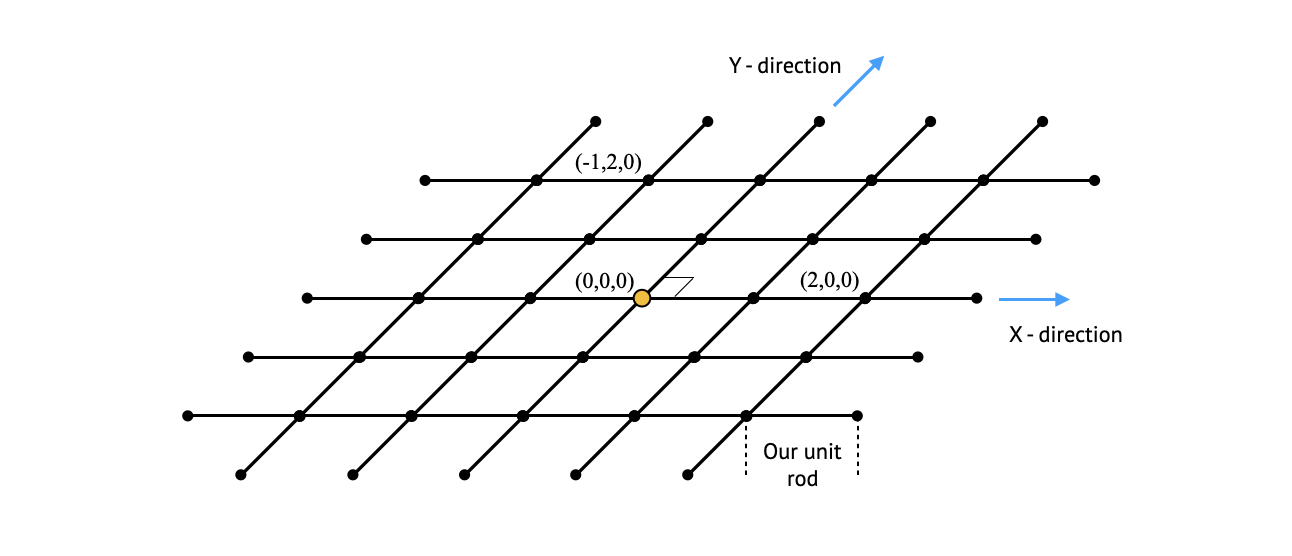

To construct the Y-axis we go back to the origin and choose an arbitrary direction which has a 90 degree angle relative to the X direction. By placing the rod along this direction, in a similar manner as before, we can map out the Y-axis, which will define the points in space labeled as $(0,1,0), (0,2,0)$ and so on. If instead of starting this process from the origin we would start it from the point (1,0,0), we would get all the points in space labeled as $(1,1,0), (1,2,0)$ and so on. Finally, by going back to the origin and choosing a third direction which is perpendicular to both the X-axis and the Y-axis, and repeating our tiling process, we define the Z-axis with all points of the form $(0,0,1), (0,0,2)$ and so on. Defining a length smaller than one unit can be achieved by dividing the rod into equal length parts, with as many parts as we want to achieve any desired precision. Thus, the above process results in a coordinate system for which any point $(x,y,z)$ corresponds to a position in space.

The above construction however hides an implicit assumption: we reached the point $(1,1,0)$ by starting from $(1,0,0)$ and “turning left and moving one unit”. If instead we would start from the point $(0,1,0)$ and “turn right and move one unit”, we expect to reach the same point in space. This is of course true also for any other coordinate – we expect to reach the same physical point in space regardless of the path we took to reach it. It is possible to check whether this is true or not by using the tools we have – we can choose an arbitrary point in space, and try to reach it along different paths. If every time we do so we will reach the same point in space, we will eventually convince ourselves that our coordinate system is valid – every unique label $(x,y,z)$ does indeed corresponds to a unique position in space. In this case we would say that the space we inhabit is ‘flat’.

Constructing time coordinates

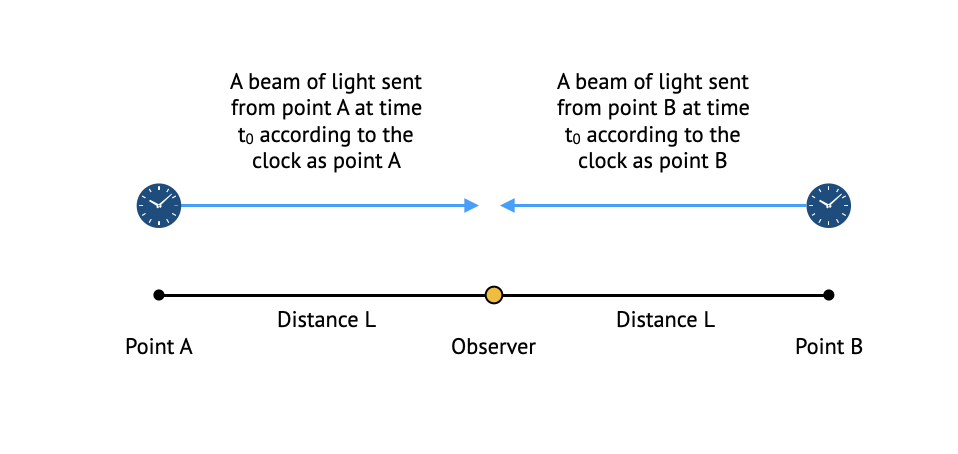

What about the time coordinate? Well, for this of course we need a clock. Suppose we have a “unit clock”, similar to the unit rod we used the map space. This clock gives us time coordinates: a label for each point in time, marked by one tick of the clock. But if we stand at the origin with our clock, how can we assign time labels in other points in space? For this we would need to place a clock at each point in space, and all these clocks must be synchronized. OK, suppose we have as many clocks as we need to make our measurements, and suppose we place one clock at each point in space, such that when the bird passes a given point, we can log the time this happened using the clock at this point. But how do we know these clocks are synchronized?

When mapping space using our coordinate system, we had a single rod we used to map all space. This ensured us that our grid points are “synchronized”: we can for example measure the size of an object using our coordinates and get the same answer regardless of the location of the object in space. So we need something similar with time. To achieve this, we need a method by which an observer can convince himself that two clocks at different locations in space are synchronized. This method, proposed by Einstein, is as follows: suppose we want to make sure the clocks at two points A and B are synchronized. The observer can position himself at a point which is at equal distance from both A and B. Then, a device placed at each point is set to send a beam of light towards the observer at time $t_0$, according to the clock at its point. The observer therefore will detect two beams of light: one reaching from point A and one reaching from point B. The observer can then check whether the two beams of light arrived together (at the same time). If they did, we can declare that the clocks in points A and B are synchronized. If not, they are not synchronized.

If the above experiment confirms that the clocks at any two points in space are synchronized for any time at which the experiment is performed, then the entire ‘space-time’, consisting of all ‘events’, which are nothing more than positions in both space and time, is ‘flat’.

What can we do with a coordinate system?

Now that we have our well defined coordinate system in flat space-time, we can start measuring things. If for example we have a stationary object that stays in the same place without moving, we can measure its size by noting the space coordinates of its exterior frame and doing the appropriate calculations on them. The simplest calculation is just measuring length: if an elongated object is situated such that one end of it is at position $(x_1,y_1,z_1)$ and its other end is at position $(x_2,y_2,z_2)$, then the length of this object is:

$L=\sqrt{(x_2-x_1)^2+(y_2-y_1)^2+(z_2-z_1)^2}$

If on the other hand two events occur at the same location in space but at different times, t1 and t2, we can measure the time between these events by subtracting the time stamp of each event:

$T = t_2 – t_1$

Putting both together, we can now compare two events occurring at difference places at different times. If we measured a birds position at time $t_1$ to be $(x_1,y_1,z_1)$, and at time $t_2$ to be $(x_2,y_2,z_2)$ we can define the velocity of the bird to be:

$v_{bird} = \frac{L}{T} = \frac{\sqrt{(x_2-x_1)^2+(y_2-y_1)^2+(z_2-z_1)^2}}{t_2-t_1} \;\; \left[ \frac{\text{rods}}{\text{tick}} \right]$

One important thing to note here is that these measurement do not depend on our choice for the origin point, as they depend only on the difference between coordinate values. This means that if we were to shift our entire coordinate system, either in space or in time, these values would not change.

The notion of velocity is particularly important in special relativity, as the question this theory answers is how the perception of events changes for two observers who are moving at constant velocity with respect to each other. The answer to this question is the topic of our next discussion.

Changing perspectives

Up until now, the coordinate system that we’ve built was relative to a single observer. This was the observer that tiled the entire space with his rod, made sure all clocks are synchronized and verified that the entire space-time is flat. All measurements done using this constructed coordinate system are therefore relative to that observer, or phrased differently: are with respect to this observer’s ‘frame of reference’.

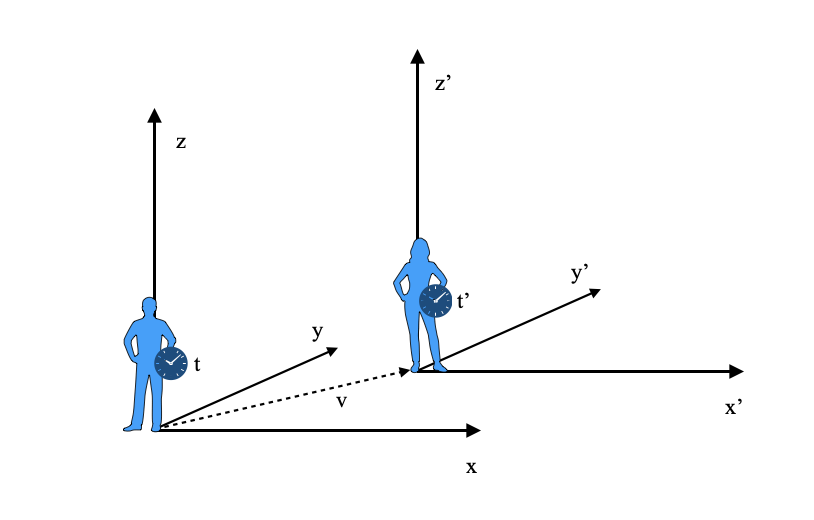

But what happens if we change perspective to a different observer? The space-time itself is not observer dependent, it consists of events on which all observers agree upon: if the bird landed on a branch, and caused a leaf to fall and hit the ground, this is a sequence of events that occurred in the physical space-time regardless of any observer observing it. Let’s say our first observer records the event of the bird landing on a branch as occurring at space-time coordinate $(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0)$. Now suppose we have a different observer that borrowed the rod and clock from our first observer and used it to construct a different coordinate system, or frame of reference, which we will denote O’. In this frame of reference the second observer logged the event of the bird landing on the branch as occurring at coordinate $(t_0′,x_0′,y_0′,z_0′)$. What is the relation between $(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0)$ and $(t_0′,x_0′,y_0′,z_0′)$? How can we switch from one to the other?

Since we chose an arbitrary event, we can generalize the discussion by omitting the coordinates subscripts and just investigate the general transformation rule from the coordinates $(t,x,y,z)$ to $(t’,x’,y’,z’)$. Starting from a simple scenario, let’s assume that the second observer is standing still at the space coordinate $(1,0,0)$, and that the time origin of both observers at their respective spatial origin is synchronized. In this case the transformation would be:

$\begin{align} t’ &= t \\ x’ &= x – 1 \\ y’ &= y \\ z’ &= z \end{align}$

That’s easy and boring enough. Where it gets more interesting is when we consider a different scenario, in which the second observer is moving with a constant velocity $v$ with respect to the first observer:

In this case, we refer to the second observer as an ‘inertial’ observer. Assuming the origins of both observers are aligned, and assuming for the sake of simplicity that the motion is strictly in the X-direction, we would expect that the coordinate transformation would take the form:

$\begin{align} t’ &= t \\ x’ &= x – vt \\ y’ &= y \\ z’ &= z \end{align}$

Why? Because after $t$ clock ticks the second observer would be at distance $vt$ compared to our first observer, and the same logic applied to the previous case is applied in the same manner here. This transformation, which is now referred to as ‘Galilean transformation’, was the one assumed to be true in the physics community from the days of Newton up until the early 20’th century. But alas, it turns out that nature operates by different rules.

In the next part of the series we will develop the the Lorentz transform, which gives us the coordinate transformation rule that leads to correct physical predictions.

Pingback: Special Relativity Part II: The Lorentz Transform - foundational.site