In the previous part we’ve constructed a coordinate system, which provided us with a consistent way with which an observer can make measurements of events occurring in physical space-time. We also saw how we can measure length, time and velocity using our coordinate system. In this part we will discuss how the measured coordinates of a given event taken in two reference frames, which are moving at constant speed with respect to each other, change. The coordinate transformation between two co-moving observers is referred to as a ‘boost’, in distinction from other coordinate transformations such as rotation, reflection and translation, which we will also use in this part.

In 1905 Albert Einstein formulated the two postulates of special relativity, which are:

- The principle of relativity: The laws of physics are the same in any inertial frame of reference.

- The constancy of the speed of light: The speed of light in a vacuum is the same for all inertial observers.

These postulates will provide the underlying principles from which we will next derive the Lorentz transform.

Boosting is a linear transformation

To distinguish between our two observers, we will denote the reference frame of the first observer as $\mathcal{O}$, and the reference frame of the second observer, which is moving at velocity $v$ in the first observers reference frame, as $\mathcal{O}’$. Our mission is therefore to find the relation between the coordinates $(t,x,y,z)$ in $\mathcal{O}$ to the coordinates $(t’,x’,y’,z’)$ in $\mathcal{O}’$.

In general, the boost transformation can be written as:

$\begin{align}

t’ &= f_t \left(t, x, y, z \right) \\

x’ &= f_x \left(t, x, y, z \right)\\

y’ &= f_y \left(t, x, y, z \right) \\

z’ &= f_z \left(t, x, y, z \right)

\end{align}$

And we want to find the functions $f_t(), f_x(), f_y(), f_z()$. Let’s start with a guess. Suppose the function $f_x()$ is given by:

$f_x(t,x,y,z) = t^2x^2 + y + z$

Now let’s consider two events which in $\mathcal{O}$’s reference frame occurred at coordinates $(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0)$ and $(t_0+\Delta t,x_0+\Delta x,y_0,z_0)$, i.e. they occurred at distance $\Delta x$ from one another and the time passed between them is $\Delta t$. What about our second observer? Well, using our guessed function, the distance between these events along the $x’$ axis would be:

$\Delta x’ = f_x(t_0 + \Delta t,x_0 + \Delta x,y_0,z_0) – f_x(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0) = t_0^2 \Delta x^2 + x_0^2 \Delta t^2 + \Delta x^2 \Delta t^2$

But there is a problem here. The values $(t_0,x_0)$ depend on our choice of origin, and are therefore arbitrary. We would not expect that changing the arbitrary origin of one reference frame will change the distance between two events in another reference frame. To avoid this problem, we need to impose the following requirement on our boost function:

When moving from one reference frame to another, the coordinate difference between two events in the second reference frame depends only on the coordinate difference between these events in the first reference frame

Mathematically, we can formulate this constraint as follows:

$f_x\left(t_0 + \Delta t,x_0 + \Delta x,y_0 + \Delta y,z_0 + \Delta z\right) – f_x\left(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0\right) = g\left(\Delta t,\Delta x,\Delta y,\Delta z\right)$

Where g() is some unknown function. Let’s analyze a scenario in which only $\Delta x$ is non zero. In this case, we can use Taylor expansion to write g() as a general polynomial in $\Delta x$:

$g\left(0,\Delta x,0,0\right) = g_0 + g_1\Delta x + g_2 \Delta x ^2 + g_3 \Delta x^3 + …$

We can immediately determine that $g_0 = 0$, as otherwise we will get that $\Delta x’$ is not $0$ when measuring the distance between an event to itself. To figure out what form the function $f()$ takes under our new constraint, we can divide both sides of the equation above by $\Delta x$ to get:

$\frac{ f_x\left(t_0,x_0 + \Delta x,y_0,z_0\right) – f_x\left(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0\right) }{\Delta x} = \frac{ g_1\Delta x + g_2 \Delta x ^2 + g_3 \Delta x^3 + … } { \Delta x }$

As you’re probably guessing, next we will take $\Delta x$ to be arbitrarily small, giving us the derivative of $f_x()$ with respect to $x$:

$\frac{ \partial f_x\left( t, x, y, z \right) }{\partial x} \big|_{t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0} = g_1$

Since $g()$ itself does not depend on the choice of the specific point $(t_0,x_0,y_0,z_0)$, we get that the derivative of the boost function with respect to $x$ is constant. We could have of course done the same exercise on the coordinates $t$, $y$ or $z$, as well as on the functions $f_t()$, $f_y()$ or $f_z()$, and reach the same conclusion: the derivatives of these functions with respect to any of their inputs is constant. This in turn implies that these functions are linear, and can be written as:

$f\left(t,x,y,z\right) = a_{0} + a_{1}t + a_{2}x + a_{3}y + a_{4}z$

And putting it all together in matrix notation gives:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \\ y’ \\ z’ \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24} \\

a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34} \\

a_{41} & a_{42} & a_{43} & a_{44} \\

\end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right] + \left[ \begin{matrix} a_{10} \\ a_{20} \\ a_{30} \\ a_{40} \end{matrix} \right]$

This is a huge simplification. Instead of dealing with four general 4-dimensional functions, we’re now left with 20 unknown coefficients. Our remaining task is now to find these 20 coefficients.

Simplifying the setup

To pin down the exact boost function, we are going to make our lives easier by applying some simplifying steps. Our first simplifying step will be to align the origins of the two reference frames. In a given reference frame, we can easily change the origin mathematically by adding a constant term to any axis. We can therefore add the required offsets such that the origin of both frames of reference will correspond to the same event in space-time. If the origins are aligned, it means that $(0,0,0,0)$ in $\mathcal{O}$ should be mapped to $(0,0,0,0)$ in $\mathcal{O}’$. This forces the constant offset term to be zero, and we remain with the following boost transformation:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \\ y’ \\ z’ \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix} a

a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24} \\

a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34} \\

a_{41} & a_{42} & a_{43} & a_{44} \\

\end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

Next, we’re going to assume that the main spatial axis of $\mathcal{O}$ and $\mathcal{O}’$ are aligned. If this is not the case, we can perform a combination of 3-D rotations and reflections on $\mathcal{O}’$ to spatially align in to $\mathcal{O}$. Next, we’re going to assume that the movement of $\mathcal{O}’$ with respect to $\mathcal{O}$ occurs along the $x$ direction of both reference frames. This is also not a major restriction, as if this is not the case, we can rotate both $\mathcal{O}$ and $\mathcal{O}’$ such that the direction in which $\mathcal{O}’$ is moving with respect to $\mathcal{O}$ is along the $x$-axis. So to recap – in the general case we have applied three transformations on our reference frames:

- We have moved the origin of $\mathcal{O}’$ to coincide with the origin of $\mathcal{O}$

- We have rotated and reflected $\mathcal{O}’$ to align its axis to $\mathcal{O}$

- We have rotated both $\mathcal{O}$ and $\mathcal{O}’$ such that the movement of $\mathcal{O}’$ with respect to $\mathcal{O}$ is along the $x$-axis

All these transformation are reversible, and are performed independently on each reference frame. They are therefore completely indifferent to the physical space-time and do not cause any loss of generality. Since we also did not stretch the axis, these transformations do not change the space and time units of measurements.

Transforming the perpendicular directions

Let’s go back to our general boost function and use our simplified setup to analyze the transformation parts related to the $y$ and $z$ directions. The motion between our observers is strictly in the $x$ direction, so we may expect something to change in this direction. However, the $y$ and $z$ directions are both perpendicular to the relative motion, and we are free to choose their orientation in our coordinates system without it changing anything meaningful about the setup. This means that either rotating the $y$-$z$ plane by some angle $\theta$, or flipping one or both of these axis, should have no effect on the boost function as long as we apply the same transformation to both observers. As we will now see, this freedom can help us figure out the boost coefficients related to these directions.

We will start with rotation: suppose we rotate the $y$-$z$ plane by an angle $\theta$ in both reference frames, giving us new axis $(\hat{t},\hat{x},\hat{y},\hat{z})$ which are calculated by:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} \hat{t} \\ \hat{x} \\ \hat{y} \\ \hat{z} \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & \cos\left(\theta\right) & -\sin\left(\theta\right) \\

0 & 0 & \sin\left(\theta\right) & \cos\left(\theta\right) \\

\end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

Formalizing our above reasoning mathematically, we claim that by first boosting from the first observer to the second, and then rotating the $y$-$z$ plane, we expect to get the same result as if we were to switch the order of operations – first rotating and then boosting. Boosting and then rotating is expressed as follows:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} \hat{t}’ \\ \hat{x}’ \\ \hat{y}’ \\ \hat{z}’ \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & \cos\left(\theta\right) & -\sin\left(\theta\right) \\

0 & 0 & \sin\left(\theta\right) & \cos\left(\theta\right) \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} & a_{13} & a_{14} \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & a_{23} & a_{24} \\

a_{31} & a_{32} & a_{33} & a_{34} \\

a_{41} & a_{42} & a_{43} & a_{44} \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

Rotating and boosting simply switches between the two matrices. The resulting rotated coordinates in the second observers reference frame for each case are summarized in the table below:

| Coordinate | Boost and rotate | Rotate and boost |

|---|---|---|

| $\hat{t}’$ | $a_{11}t + a_{12}x + a_{13}y + a_{14}z$ | $\begin{align} &a_{11}t + a_{12}x + \\ &a_{13}( \cos(\theta) y – \sin(\theta) z ) + \\ &a_{14}( \sin(\theta) y + \cos(\theta) z) \end{align}$ |

| $\hat{x}’$ | $a_{21}t + a_{22}x + a_{23}y + a_{24}z$ | $\begin{align} &a_{21}t + a_{22}x + \\ &a_{23}( \cos(\theta) y – \sin(\theta) z) + \\ &a_{24}( \sin(\theta) y + \cos(\theta) z) \end{align}$ |

| $\hat{y}’$ | $\begin{align} &\cos(\theta) ( a_{31}t + a_{32}x + a_{33}y + a_{34}z ) – \\ &\sin(\theta) ( a_{41}t + a_{42}x + a_{43}y + a_{44}z )\end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{31}t + a_{32}x + \\ &a_{33} ( \cos(\theta) y – \sin(\theta) z ) + \\ &a_{34} ( \sin(\theta) y + \cos(\theta) z )\end{align}$ |

| $\hat{z}’$ | $\begin{align} &\sin(\theta) ( a_{31}t + a_{32}x + a_{33}y + a_{34}z ) + \\ &\cos(\theta) ( a_{41}t + a_{42}x + a_{43}y + a_{44}z )\end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{41}t + a_{42}x + \\ &a_{43} ( \cos(\theta) y – \sin(\theta) z ) + \\ &a_{44} ( \sin(\theta) y + \cos(\theta) z )\end{align}$ |

Since we should reach the same result in both cases for any value of $(t,x,y,z)$, the coefficient of any input coordinate in the expression for any output coordinate must be equal for any angle $\theta$. This gives us 16 equations involving our unknown coefficients, with a free parameter $\theta$. These equations, after some simplifications, are summarized in the table below:

| $t$ | $x$ | $y$ | $z$ | |

| $\hat{t}’$ | $a_{11} = a_{11}$ | $a_{12} = a_{12}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{13}(1 – \cos(\theta)) = \\ &a_{14}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{14}(\cos(\theta) – 1) = \\ &a_{13}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ |

| $\hat{x}’$ | $a_{21} = a_{21}$ | $a_{22} = a_{22}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{23}(1 – \cos(\theta)) = \\ &a_{24}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{24}(\cos(\theta) – 1) = \\ &a_{23}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ |

| $\hat{y}’$ | $\begin{align} &a_{31}(\cos(\theta) – 1) = \\ &a_{41}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{32}(\cos(\theta) – 1) = \\ &a_{42}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &-a_{43}\sin(\theta) = \\ &a_{34}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{44}\sin(\theta) = \\ &a_{33}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ |

| $\hat{z}’$ | $\begin{align} &a_{41}(1 – \cos(\theta)) = \\ &a_{31}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{42}(1 – \cos(\theta)) = \\ &a_{32}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{33}\sin(\theta) = \\ &a_{44}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ | $\begin{align} &a_{34}\sin(\theta) = \\ &-a_{43}\sin(\theta) \end{align}$ |

Starting with the $(t’,y)$ equation, by choosing $\theta = \pi$ we get $2a_{13} = 0$, which means that $a_{13} = 0$. Similar reasoning applied to the $(t’,z)$, $(x’,y)$, $(x’,z)$, $(y’,t)$, $(y’,x)$, $(z’,t)$ and $(z’,x)$ equations will quickly show that we also must have $a_{14} = a_{23} = a_{24} = a_{31} = a_{32} = a_{41} = a_{42} = 0$.

We’re left with four coefficients. The $(y’,z)$ and the $(z’,y)$ equations both tell us that $a_{33} = a_{44}$, and the $(y’,y)$ and $(z’,z)$ both shows us that $a_{34} = -a_{43}$. To pinpoint these last two coefficients, we can consider a flip of the y-axis instead of rotation of the $y$-$z$ plane. Substituting the coefficients we’ve already found, boosting and flipping the $y$-axis is expressed as follows:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} \hat{t}’ \\ \hat{x}’ \\ \hat{y}’ \\ \hat{z}’ \end{matrix} \right] = \left[ \begin{matrix}

1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} & 0 & 0 \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & a_{33} & a_{34} \\

0 & 0 & -a_{34} & a_{33} \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

As before, we expect that switching the order of operations, which translates to switching the matrices in this expression, will result in the same coordinates for any point we boost. Running the calculation, we get the following equation, which must hold for any $(y,z)$:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} \hat{y}’ \\ \hat{z}’ \end{matrix} \right] =

\left[ \begin{matrix} -a_{33}y – a_{34}z \\ -a_{34}y + a_{33}z \end{matrix} \right] =

\left[ \begin{matrix} -a_{33}y + a_{34}z \\ a_{34}y + a_{33}z \end{matrix} \right]$

Looking at both expressions for $\hat{y}’$ we see that for any non-zero value of $z$ we must have that $a_{34} = -a_{34}$, which tells us that $a_{34} = 0$. So our boost function is reduced to:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \\ y’ \\ z’ \end{matrix} \right] =

\left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} & 0 & 0 \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & a_{33} & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & a_{33} \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

So far we’ve made some good progress. Putting aside the $(x,t)$ transformation, we started with 12 unknown coefficients related to the $y$-$z$ boost, and by applying symmetry constraints we were able to reduce them into one unknown coefficient. How can we resolve this one remaining coefficient? Well, like we did before, let’s start with a guess.

Let’s say the value of the coefficient is 1/2. This means that if the first observer measures an event occurring at distance 1 meter in the $y$ direction, from the second observer’s perspective this event occurred at a distance of 1/2 a meter in the $y$ direction. Now, let’s consider the opposite boost, which transforms the coordinates of the second observer to the ones of the first observer. Since there is no preferred observer, all the discussion so far applies also to the boost function from the second observer to the first. We can therefore conclude that the transformation of the $y$ coordinate in the reverse boost takes the form:

$y = a’y’$

With some unknown parameter $a’$. We also know that boosting from the first observer to the second, and then boosting back, should recover the original $y$ value, so we have:

$y = a’ay$

Which implies that $aa’ = 1$. So if $a$ = 1/2 we must have $a’$ = 2.

Does it make sense that we have a different coefficient for the reverse transform? Well, there is no a-priory reason to assume $a$ must be constant for any boosting between two inertial observers. The coordinate transformation between two observers can after all depend on the velocity between them – both its magnitude and direction. If the second observer moves at velocity $v$ in the first observers reference frame, the first observer moves at velocity $-v’$ in the second observer’s reference frame. So as a consequence of our initial guess, it would seem that for a positive value of $v$ we get $a < 1$, and for negative value of $v$ we get $a > 1$. But this is a problem. The reason being that the sign of the velocity depends on the orientation of the $x$-axis, but this orientation is arbitrary. We can flip the $x$-axis of both observers without changing anything about the physics, so we would not expect this change to alter the boost coefficient of the perpendicular $y$ direction. But after flipping the $x$-axis, the sign of the velocities of the observers with respect to each other will also flip, and if we insist to stick to our guess it would mean we will need to change the $a_{33}$ coefficient of the boosts. So the conclusion we arrive at is that $a_{33} = 1$, which means that no change in coordinate occurs in either the $y$ or $z$ direction.

The Lorentz transformation

The discussion up until now resulted in a transformation rule of the form:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \\ y’ \\ z’ \end{matrix} \right] =

\left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} & 0 & 0 \\

a_{21} & a_{22} & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \\ y \\ z \end{matrix} \right]$

Focusing only on the $t$ and $x$ coordinates, we are left with just:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \end{matrix} \right] =

\left[ \begin{matrix}

a_{11} & a_{12} \\

a_{21} & a_{22} \\

\end{matrix} \right]

\left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \end{matrix} \right]$

Putting aside the physics for a moment, what we have here is just a linear transformation in a 2-dimensional real vector space, which is defined by four free parameters. The good thing about this is that to find the exact transformation, it is enough to come up with four independent equations involving these parameters, which we can then solve. To accomplish this we will devise two experiments, and use Einsteins second postulate to relate specific events between our two observers.

Experiment 1

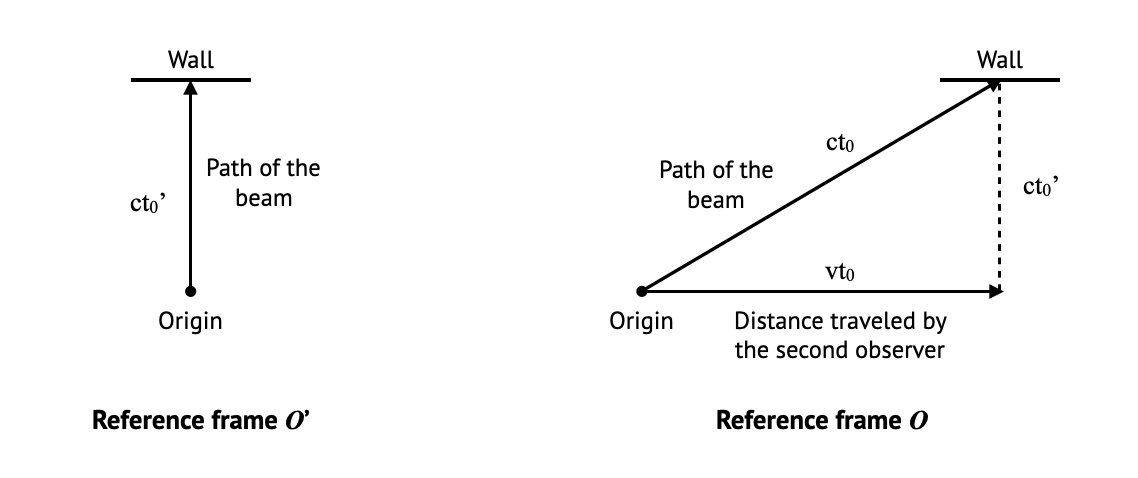

For the first experiment, let’s imagine a beam of light transmitted from the origin by the second observer in the $y$ direction, and hitting a wall after some time $t_0’$. From the second observers perspective, the beam only moved in the $y$-direction, and the event of the beam hitting the wall occurred at $(t’,x’,y’,z’) = (t_0’,0,ct_0’,0)$.

From the first observers perspective, the beam moved for some time $t_0$ along a diagonal line of length $ct_0$, as the speed of light does not change between the observers. In the $x$-direction, the beam progressed a distance of $vt_0$, as it simply moved with the second observer. In the $y$-direction, it moved the same distance as it did for the second observer, since, as we proved in the last part, no change occurs between observers in this direction. So for the first observer, the event of the beam hitting the wall occurred at $(t,x,y,z) = (t_0,vt_0,ct_0’,0)$:

The path of the beam in $\mathcal{O}$ draws a right sided triangle. This allows us to relate $t_0$ and $t_0’$ using Pythagoras theorem:

$\left( vt_0 \right)^2 + \left( ct_0′ \right)^2 = \left( ct_0 \right)^2$

Which we can solve for $t_0’$ and get:

$t_0′ = t_0 \sqrt{1 – \frac{v^2}{c^2}}$

To simplify the notation, we will define the constant $\gamma$ to be:

$\gamma = \frac{1}{ \sqrt{1 – \frac{v^2}{c^2}} }$

So the relation we found can be written as $t_0’ = \gamma^{-1}t_0$. This relation holds for any $t_0$, as we can change the height of the wall as we want. We can therefore assume a specific scenario in which $t_0 =1$. Ignoring the $y$ and $z$ coordinates, we conclude that the point $(t,x) = (1,v)$ maps to $(t’,x’) = (\gamma^{-1},0)$. But on the other hand according to our formulation this point maps to $(t’,x’) = (a_{11}+a_{12}v, a_{21}+a_{22}v)$, and this gives us two equations with our unknown transformation parameters:

$\begin{align}

a_{11} + a_{12}v &= \gamma^{-1} \\

a_{21} + a_{22}v &= 0

\end{align}$

We can now continue to the second experiment.

Experiment 2

The second experiment we’ll analyze is one in which the first observer emits a beam of light from the origin in the $x$-direction, which hits a wall after 1 second ($t = 1$). The distance passed in $\mathcal{O}$ is $c$ meters, so the event of the beam hitting the wall occurred at the point $(t,x) = (1,c)$.

In $\mathcal{O}’$ reference frame the beam was also emitted from the origin, and the event of it hitting the wall occurred at some point $(t_1’,x_1’)$. What can we say about this point? Well, according to Einsteins second postulate, the speed of the light beam is $c$ also in $\mathcal{O}’$, and since $x_1’$ is the distance passed by the beam in time $t_1’$, we conclude that:

$\frac{x_1′}{t_1′} = c$

But on the other hand, according to our transformation rule this point is also given by $(t’,x’) = (a_{11}+a_{12}c, a_{21}+a_{22}c)$. And by putting these two together we get that:

$\frac{a_{21} + a_{22}c}{a_{11} + a_{12}c} = c$

Or:

$a_{21} + a_{22}c – a_{11}c – a_{12}c^2 = 0$

And we have our third equation.

For the last equation, we can consider a similar experiment, but with the beam transmitted in the opposite direction. After 1 second in $\mathcal{O}$ it reaches a distance $x = -c$. In $\mathcal{O}’$ the velocity of the same beam is also $-c$, so by applying the same procedure as before we arrive at the following equation:

$a_{21} – a_{22}c + a_{11}c – a_{12}c^2 = 0$

And we have our fourth equation. All that’s left to do now is to solve them.

Solving the equations

Let’s summarize our findings from these experiments in a table:

| Event | $(t,x)$ | Derived equations |

|---|---|---|

| A beam emitted by the second observer from the origin in the $y$ direction hits a wall after 1 second in the first observer frame of reference | $(1,v)$ | $\begin{align} a_{11} + a_{12}v &= \gamma^{-1} \\ a_{21} + a_{22}v &= 0 \end{align}$ |

| A beam of light emitted by the first observer from the origin in the $x$-direction hits a wall after 1 second | $(1,c)$ | $a_{21} + a_{22}c – a_{11}c – a_{12}c^2 = 0$ |

| A beam of light emitted by the first observer from the origin in the negative $x$-direction hits a wall after 1 second | $(1,-c)$ | $a_{21} – a_{22}c + a_{11}c – a_{12}c^2 = 0$ |

By rearranging the terms we arrive at the following four equations on the unknown transformation parameters:

$\begin{matrix}

&&&&&a_{11} &+ &a_{12}v &= &\gamma^{-1} \\

&a_{21} &+ &a_{22}v &&&&&= &0 \\

&a_{21} &+ &a_{22}c &- &a_{11}c &- &a_{12}c^2 &= &0 \\

&a_{21} &- &a_{22}c &+ &a_{11}c &- &a_{12}c^2 &= &0

\end{matrix}$

Solving them is a straight forward task. Let’s run by it quickly. Adding and subtracting equations (3) and (4) gives us the simplified equations:

$\begin{align}

a_{21} &= a_{12}c^2 \\

a_{22} &= a_{11}

\end{align}$

Substituting into equations (1) and (2) gives us:

$\begin{align}

a_{11} + a_{12}v &= \gamma^{-1} \\

a_{12}c^2 + a_{11}v &= 0 \\

\end{align}$

Substituting the second equation into the first one gives us:

$a_{11} \left(1 – \frac{v^2}{c^2} \right) = \gamma^{-1} \;\; \Rightarrow \;\; a_{11} = \gamma$

And substituting back to the other equations gives:

$a_{22} = \gamma \; ; \; a_{12} = -\frac{v}{c^2} \gamma \; ; \; a_{21} = -v\gamma$

And now we have finally arrived at the space-time coordinate transformation between two inertial reference frames, better known as the Lorentz transformation, given by:

$\left[ \begin{matrix} t’ \\ x’ \end{matrix} \right] = \gamma\left[ \begin{matrix}

1 & -\frac{v}{c^2} \\

-v & 1 \\

\end{matrix} \right] \left[ \begin{matrix} t \\ x \end{matrix} \right]$

And this is a good place to stop for now.

Summary

It was certainly a long ride, so let’s briefly recall the steps we have taken to arrive at the Lorentz transform, assuming our simplified setup and starting from a completely general transformation function:

| Step | Argument | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The distance between events after boosting should depend only on the distance between events before boosting | The boost transformation is a linear transformation |

| 2 | Boosting should be indifferent to rotation or reflections of the $y$-$z$ plane | The $y$ and $z$ coordinates can only be stretched or contracted |

| 3 | The $y$ and $z$ transform should be indifferent to flipping of the $x$-axis | The $y$ and $z$ coordinates do not change |

| 4 | The speed of light is identical for all observers | $x$ and $t$ transform according to Lorentz transformation |

In the next parts, we will explore some of the weird physical phenomena that result from this transformation. Thank you for reading.